THE BATTLE OF NASHVILLE

By Ross Massey, BONT Historian

Preface:

After the battles for Chattanooga, Union troops pursued the Confederate forces to Atlanta, Georgia. After four unsuccessful attacks against the Union, Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood abandoned Atlanta in September 1864 and retreated into Alabama. There Hood devised an ambitious plan to cut off Union supply lines coming south from Tennessee and starve the Union troops in Georgia into surrender. He planned to take Nashville, which had been occupied by the Federals since early 1862, and then move toward Louisville before joining Gen. Robert E. Lee in Virginia for the Confederacy’s grand assault on Washington, D.C.

Hood’s Strategy to Reclaim Tennessee

If Confederate General John Bell Hood had intentionally tried to destroy his army and lose the campaign to take back Tennessee, he could hardly have done a more efficient job. He entered the state with an effective force of about 34,000 men, including Forrest’s cavalry.

After the Battle of Franklin (Nov. 30, 1864), he had just 26,000 left. Before arriving outside “Fortress Nashville,” he further weakened his small army. He sent Forrest with most of the cavalry, reinforced by detachments of infantry, to deal with U.S. forces at Fortress Rosecrans outside Murfreesboro. He even sent a depleted brigade of Missouri Confederate regiments off to build a fort on the Tennessee River.

This left only about 21,000 men at Nashville. He knew the city had been heavily fortified by the U.S. Army, and he could not make another offensive strike like at Franklin. Instead, he threw up defensive works, roughly parallel to today’s I-440, and waited to be attacked.

He hoped to defeat any attacks, then counterattack, and retake the city. Even a victorious defense typically results in enough confusion to rule out immediate counterattacks. So, his plan had very little chance of success.

Hood worsened his situation by making his lines too long. To repel an assault it is desirable to maximize firepower along your lines. Hood’s main line was about five miles long. There were about 20,000 men behind it as his remaining cavalry was detached on his flanks. He had an average of about 4,000 men per mile.

In comparison, at Gettysburg, the U.S. Army had four times as many men in only three miles, for an average of 27,000 men per mile. Hood might have learned a lesson about maximization of firepower, as he had attacked those lines at Gettysburg and had his arm shattered by a bullet.

The Federals Concentrate in Nashville

Opposing Hood’s thin, ragged line was U.S. General George Thomas and his large, well-equipped army.

During this time, Sherman was carrying on an incendiary campaign against the citizens and businesses of Georgia, but before setting on, he had detached Thomas to deal with Hood. Thomas’s job was to assemble an army to hold Nashville and destroy Hood.

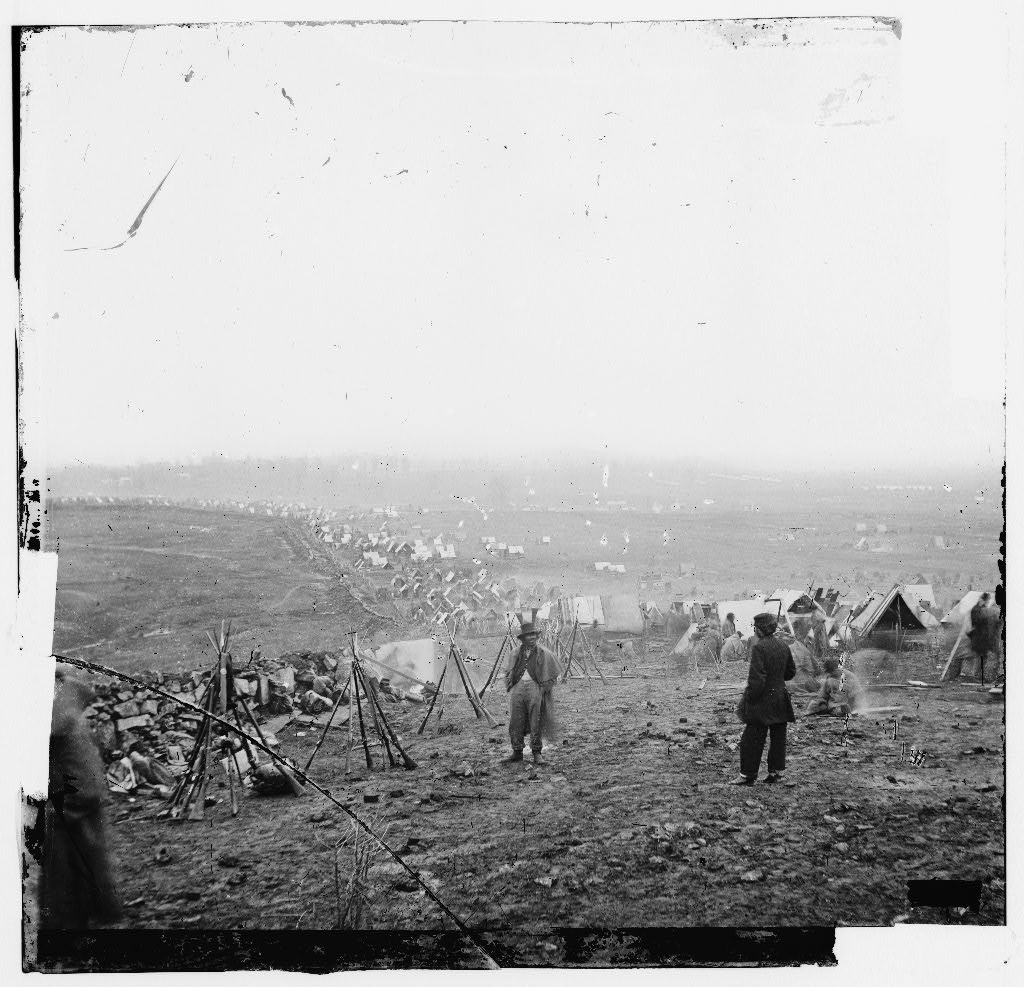

The basis of this army was Schofield’s forces, which had battled Hood at Franklin. While they delayed Hood, Thomas had time to pull in various detachments scattered about Tennessee and surrounding states. An entire Army corps was brought from Missouri by a fleet of steamboats. A huge cavalry corps of over 12,000 effectives was organized. Their critical role in the battle was enhanced by a new invention, repeater rifles.

In all, U.S. forces exceeded 70,000 soldiers. Over 55,000 men were used offensively against Hood, while the rest held the fortifications around Nashville.

Yet, for two weeks this army was unable to move, being held up by an early, unseasonable storm of ice and snow. While they waited for a thaw, housed in barracks and tents, Hood’s army waited as well, though with less favorable surroundings.

Suffering and Hardships in the Cold

Valley Forge has long symbolized the pain and suffering endured by the Continental Army in the American colonists’ successful attempt to gain their independence from Britain. Similarly, the Battle of Nashville and the subsequent retreat from Tennessee may well symbolize the Confederate soldier’s misery in their unsuccessful attempt to secure independence from the United States.

Consider that George Washington’s men lacked sufficient food and clothing. He estimated that about 26 percent of his men lacked shoes while snowbound there. Some estimates of shoeless Confederates at Nashville range up to 33 percent. A Mississippi colonel said his heart almost bled seeing the traces of blood on the ground, left “from the barefoot feet of our brave soldiers.”

A Georgia lieutenant had a detail of 80 men, and said, “Not a man in that company had shoes on his feet, and many were without a blanket.” A Tennessean said, “We bivouac on the cold and hard-frozen ground, and when we walk about, the echo of our footsteps sound like the echo of a tombstone. The earth is crusted with snow, and the wind from the northwest is piercing our very bones. We can see our ragged soldier, with sunken cheeks and famine glistening eyes.”

While camped at Valley Forge, the Continental Army fought no battles, and found enough timber to contruct log cabins. The unlucky Confederates found themselves encamped on cleared agricultural land, previously stripped of most of its remaining timber by the U.S. Army.

How did they survive?

In 1983, archaeologists digging along the I-440 route provided some answers. They found hearths at only six foot intervals. It is easy to believe a Florida Confederate who said he experienced the coldest weather of his life at Nashville.

Civilians See Soldiers as Their Saviors

Another similarity between Nashville and Valley Forge is the commitment of soldiers from a wide geographic area. The Continental Army had men from all 13 colonies at Valley Forge. Of the eleven Confederate states, only Virginia was not represented at Nashville.

The Old Dominion state had troubles of its own in the city of Richmond. Robert E. Lee knew his ragged army could not hold out indefinitely. Though Virginia was not represented, her sister state of Maryland was, with an artillery battery. Actually, Maryland wanted to be a Confederate state, but Abraham Lincoln had jailed their pro-secession legislators, and even the mayor of Baltimore, to prevent it.

One sad dissimilarity between Valley Forge and Nashville was the citizenship. The determined colonial solider found the region about their camp, outside Philadelphia, unfriendly to them. The citizens around Nashville, on the other hand, were quite friendly. Having endured the occupation by U.S. troops for more than two-and-a-half years, they viewed the Confederate soldiers as their saviors.

Homes all across the countryside welcomed the army. General Hood had excellent accommodations at Traveler’s Rest. Mrs. John Overton said having the Confederate generals dine at her table was the proudest moment of her life. Over at Belle Meade, the cavalry general Chalmers and his staff were treated to snow ice cream.

Haunting Memories of Slaughter

With so many hardships to endure, the Confederate soldier was also burdened with the haunting recent memory of Franklin. They had previously suffered high casualties. In the two days of fighting at Shiloh, the Confederate army had 1,728 killed. Two days of Chickamauga left 2,312 killed. These battlefields covered over 4,000 heavily wooded acres, so that the full impact of the carnage was diluted.

But at Franklin, 1,750 Confederates were killed in one evening, and nearly all in one relatively small, open space, the Carter House lawn and farmyard. After seeing this pointless waste of their friends and relatives, they were expected to fight the Battle of Nashville.

Before sunrise, on Thursday, December 15, 1864, General Thomas walked down to the lobby of the Hotel Saint Cloud. He checked out, paying his bill, as if he didn’t anticipate returning. He stepped out onto Church Street, where gas lights burned amidst a heavy fog.

After much strategic planning, with Hood having the courtesy to wait outside the fortifications, Thomas was prepared to go and drive him away. This fog would steal more of the valuable daylight he needed.

At six-thirty, 7,600 U.S. troops began moving out Murfreesboro Pike. The right end of the CS line was anchored in a small dirt fort near the pike, along today’s Polk Avenue, where it can still be seen. It was named Granbury’s Lunette, in honor of the Texas general killed at Franklin. Over 300 of Granbury’s men were there, but so was the corps commander, Nashville’s own General B.F. Cheatham.

As the blue-clad troops approached, Cheatham had the Texans hold their fire until the last possible moment. They unleashed a volley that settled the dispute almost instantly.

But most of the attack force, untested U.S. Colored Troops, went around the lunette and across the Nashville and Chattanooga railroad just below the cut, also visible from Polk Avenue. The Confederates watched them in the fog and arranged a trap. As they crossed the tracks, they were approaching the rear of the CS line. These men did an about-face, as another brigade lit their flank. The result was a panicky retreat which ended this sideshow to the main attack.

Main Thrust Comes Against the Left Flank

Across town, on Charlotte Pike, the primary attack was coming out of the fog. U.S. cavalry, assisted by the U.S. Navy on the Cumberland, would attempt to drive CS cavalry off the pike. Most of the U.S. cavalry, however, swung over to Harding Pike, and moved with three corps of infantry toward Hood’s left along Hillsboro Pike around today’s Green Hills Village.

As they approached the pike, an isolated dirt fort named Redoubt Four, stood in their path. It was manned by only 148 Alabamians, with four cannons, but the attackers came to a halt. Bringing up more than 24 cannons, they pounded the tiny fort, still visible today off Abbott Martin Road, for three hours. Then, 7,000 U.S. troops overwhelmed it. Shortly, they would move on, and outflank Hood’s left.

Hood Reforms His Lines

Hood had watched his left giving way from on top of Shy’s Hill. The sun was low on the horizon, out past Charlotte Pike, where his cavalry was still lunging on. His opponents figured he would retreat that night. But this was the same Hood who had his arm shattered at Gettysburg, and lost a leg at Chickamauga. He would stay, and Shy’s Hill would anchor the left end of his new line.

The new line was much shorter, stretching from Shy’s Hill, alongside today’s Harding Place, over to Peach Orchard Hill, which now overlooks I-65. Thomas would use a similar plan on December 16 to overlap the CS left, around Shy’s Hill, but first, he would test Peach Orchard Hill.

Second Day Opens On the Right

Peach Orchard Hill, also known as Overton Hill, derived its name from being used as a peach orchard on the property of John Overton, of nearby Traveler’s Rest.

Lieutenant General Stephen D. Lee’s corps held this right end of the CS line with about 2,000 men on and around the hill. As the afternoon began, over 6,000 U.S. infantry began forming for an assault. After a massive artillery barrage, they moved forward at about three o’clock.

As they approached Lee’s line they became entangled in fallen tree tops, laid out to slow them down. As they struggled to get through, CS artillery opened fire, and the infantry rose up and poured out a deadly fire. The attackers were confused, and broke for the rear, ending their part in the battle. Local legend says it would have been possible to walk across the slope of the hill, stepping from one dead Yankee to another.

Decisive Encounter at Shy’s Hill

Yet the decisive encounter of the battle was just about to unfold at Shy’s Hill. Two U.S. infantry corps, and their cavalry, had been maneuvering for an assault. This force totaled over 40,000 men. About 5,000 CS infantry were on the left flank, with less than 1,500 around Shy’s Hill.

U.S. artillery had already made the hill a trap during the wet, misty afternoon. CS General William Bate said the shells were passing each other over the hill, coming from opposite directions.

His small force on top of the hill, mostly Tennesseans and Floridians, were likely disgusted with their predicament before the four o’clock assault. As the blue-clad troops began crossing open cornfields, they lost men quickly in killed and wounded.

But, as they began their ascent, the slope of the hill actually provided cover. As the tidal wave washed over the top, the overwhelmed Confederates had no time to retreat.

Confederate Forces Captured

Virtually the entire force was captured. All of the brigade commanders were captured. Georgia’s General Henry Jackson had made it to the stone fence along Granny White Pike, when he was captured by German speaking troops. Major Jacob Lesh, of Florida, was mortally wounded, but lingered until May in the misery of a cold U.S. prison camp.

Tennessee’s General Thomas Benton Smith was struck on the head with the butt of a sword after he surrendered. He lived for almost the next 60 years in a home for the insane due to the blow.

The hill’s namesake, Colonel William Shy, was shot in the forehead at point-blank range. When his family came up from Franklin to get his body, they found it pinned to a tree with a bayonet.

Hood’s Army Retreats

Though the CS line had held elsewhere, the fall of Shy’s Hill collapsed the line like falling dominoes. General Hood watched his army melt before him, retreating down the Franklin Pike. The battle ended Confederate hopes of reclaiming Tennessee.

The Battlefield Beneath Us

© 2001 By Robert Wayne Henderson, Jr.

Having grown up on the epicenter of the last major battle of the Civil War, the lack of information available on this most dramatic event in Nashville’s past has always amazed me.

Most people think of Appomattox, Virginia as the end of the Civil War, but it was Nashville where, for all practical purposes, the Confederacy waged its last serious offensive military operation. The loss that resulted, insured the defeat of the Army of Northern Virginia in the east, which was barely hanging on around Petersburg. After Nashville, the Confederates were forced into retreat until they would finally surrender a few months later in Virginia, North Carolina and finally Texas.

Those final events stand as a lasting image of the end of the war, and eclipsed the pivotal events of Spring Hill, Franklin and Nashville.

Due to the lack of any interpretive museum about the Battle of Nashville, most visitors to the city have no understanding of Nashville’s role during the Civil War. Many residents as well would probably be surprised to learn that there was a war fought in most of their own backyards. Unlike Chickamauga, Chattanooga, Shiloh and many other battlegrounds in Tennessee, there is little visible evidence of the battlefield that lies beneath most of west and south Nashville. Random historical markers are the only evidence of the mighty struggle that effectively ended the war in the west.

The lack of historical education on the war, and Nashville’s role in particular in it, has probably been the greatest obstacle to preservation efforts today.

Some say that the subject of the Civil War is still too controversial, and is generally dismissed as an affair that many would just as soon forget ever happened. This sentiment is probably a typical response to the population of any defeated country, but is exasperated by the lingering bitterness over slavery, as evidenced by the recent battles over some southern state flags.

Given this state of tension, it is no surprise that the media and most educational institutions steer away from the subject altogether.

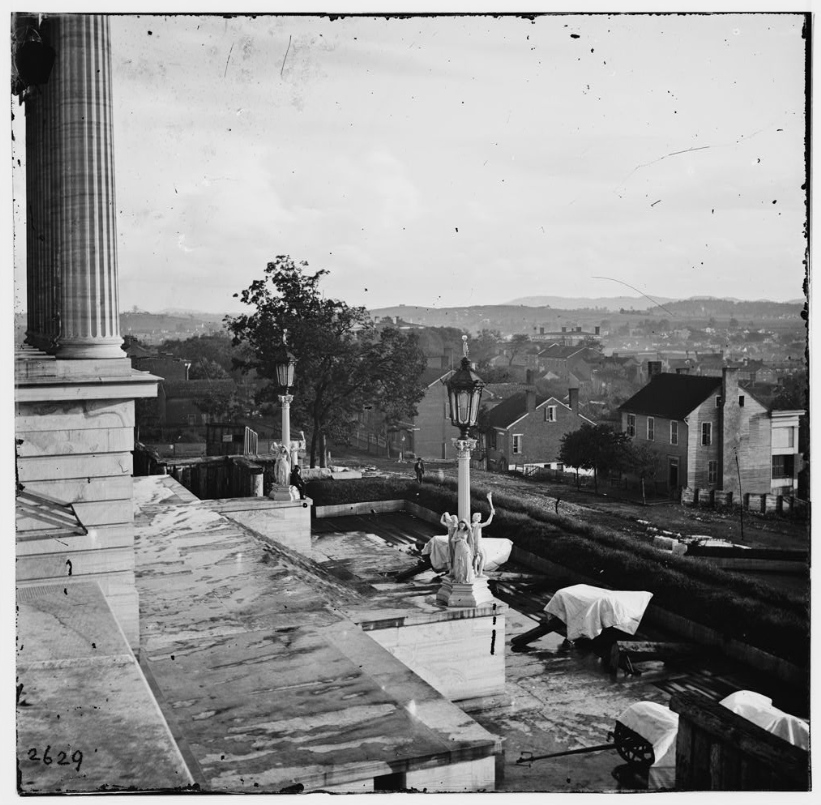

Nashville is one of the few major battlefields in the Nation that does not have a national military park. Today there is little of the battlefield available for public access.

The majority of the most significant sites have been developed for commercial or residential purposes. The old Fort Negley fortifications behind the Cumberland Science Museum in downtown Nashville, and the new Peace Monument Park on Granny White Pike, are the only Civil War landmarks in Nashville owned by the local government.

Fort Negley, which is the largest inland stone fortification of the Civil War, is in a rapid state of deterioration. There are another twenty sites around the city that can be linked to the Battle of Nashville. None are under the protection of the city, state or federal government.

As the city swells to meet the growing demand for new office space, housing and infrastructure, it risks losing what little is left of this valuable historical resource.

There is a little known site that may become the first park of its kind in Nashville — Kelley’s Battery, which is a scenic piece of real estate located on the Cumberland River nine miles west of town in a sharp bend in the river known as Bell’s Bend.

It is a well preserved wooded area, and has visible earthworks from its use as a land battery in the preceding weeks of the Battle of Nashville. A six-acre tract of the river battery site is planned to be donated to the city through negotiations between The Battle of Nashville Preservation Society, Inc., Metro Councilman Bob Bogen, and the commercial property development company that owns it: JDN Realty. The Metropolitan Park Service has expressed an interest in incorporating this land into a Greenway Park.

One hundred and thirty-seven years later, some of what little is left of this historic battlefield, might finally preserved for future generations.

A recent survey of visiting European tourists listed the Civil War as the most important attraction in Tennessee. Nashville is a perfect genesis for Civil War tours, as it has the closest international airport to the majority of Tennessee’s Civil War sites, which are second only to Virginia in the number of battlefields in the Nation. There are an estimated 1,100,000 direct descendants of Union soldiers and 470,000 direct descendants of Confederate soldiers who fought in the Battle of Nashville.

Nashville is the closest major battle site to 11 northern states which sent soldiers here to fight. Unfortunately, there is not much for the tourist to see interpreting this pivotal event in American history.

The Tennessee State Museum in Nashville is estimated to have only 10% of the state’s Civil War artifacts on display. It has a very nice war section, but not very much information on the specifics of the Battle of Nashville or Franklin.

As the city looks for new sources of tourism dollars, there is a wealth of drama, history and heritage that is a priceless cultural and economic resource to be shared with the rest of the Nation.

Preservation of Nashville’s valuable battlefield real estate should be a higher priority in the allocation of funding for historical preservation. When these historic sites are developed, they are lost forever. Erasing these sites cannot remove that painful experience from the city’s past. As troublesome as that chapter may be to some, it is a page of our city’s past that deserves more attention and respect. It is our duty as citizens to preserve these windows to the past for the benefit of us, as well as our descendants.

Understanding what transpired in generations before us, gives many clues to societal behavior today. We are, for better or for worse, influenced by those events that preceded us. It is to be hoped that by learning from these dramatic stories, we evolve a better understanding of ourselves, as well as those from whom we are descended.